| In this number I wish to tell my readers the broad reasons why the osteopathic physician has such remarkable control over the human body in all its parts and organs. You often hear this question asked in a sort of surprise that this should be so. You will often hear intelligently curious persons wonder why it is that osteopathy has made such a splendid success as a healing art. A system of therapy that has given to the world so fine a body of practitioners; that year after year is drawing larger and larger numbers of splendid men and women into the ranks of osteopathic practitioners; a system and a science that in a few years have built up so many colleges and is daily growing with a silent and steady power that is its own best recommendation has, of course, beneath it a solid foundation of scientific fact and truth. To understand this broad foundation I will ask my readers to consider for a while some intensely interesting facts of Nature, out of which the art and science of osteopathy have grown, and upon which this system rests as upon an everlasting foundation. For you must understand that osteopathy did not fall out of the sky like a meteor, but came about in the natural evolution of things just like the wireless telegraph and the electric light. The osteopathic system of therapy became possible from the moment the true structure of the nervous system was discovered, and as that discovery is most intimately associated with a broader and more fundamental discovery, I will ask my reader to follow me for a while in the relation of one of the most amazing stories that has ever been told and in the description of one of the most startling facts that has been brought to the attention of men. OUR BODIES BUILT FROM CELLS LIKE A HOUSE OF BRICKS It is now a little more than seventy years since the discovery was made that the bodies of animals, including man, consist of countless billions of microscopic animals called "cells". This epoch-making revelation startled the world when it was announced in 1839 by its discoverer, Theodor Schwann, a young German anatomist and physiologist, who at that time was assistant in the laboratory of Johannes Mueller, professor of anatomy and physiology at the University of Berlin. Previous to Schwann's discovery it had been known that plants were built up of microscopic cells, but nobody had ever suspected that the human body was constructed on the same amazing plan. To understand, in a general way of course, how the human body is constructed, peel an orange, carefully pull it apart into its constituent segments, with your fingers, take one of the smallest of these segments and gently break it across as to expose the "meat" of the orange, and then carefully examine the broken surface. The structure of the orange appears as a granular texture. By gently working at this texture you can separate the individual granules so as to remove a few of them from their countless neighbors. The granules, as you can readily see with the unaided eye, are in reality spindle-shaped or roundish bodies, like tiny bladders. Each one of these little bodies is a "cell", and the structure they form - all packed in together tightly and snugly - is a"tissue". The orange cell is one of the few forms of cell visible to the naked eye. It is a little bladder, the wall of which consists of plant fibre, and within the bladder is the sap - the protoplasm of the cell - that potent stuff of which all living matter is composed. I have said that up to Schwann's discovery it was known that plants, or vegetable bodies, were built up of cells, but it was not suspected that all animal tissues were of the same structure. Plant cells and animal cells have an infinite variety of shapes and sizes, are put together in several different ways, and are almost all individually in visible to the unaided eye. It is this difference in the shape, size and the way the cells are packed together, that form the main differences in the appearance of the different animal tissues - apart from the color and odor of the tissues. The muscles consist of billions of elongated cells, as if the cells of the orange were drawn out to invisibility and packed longitudinally together. When a great muscle, like the biceps, for example, contracts, the contraction is due to the fact that all the invisible muscle cells - called fibres - contract simultaneously together. But in order to see these individual fibres you must take some dead muscle - let us say a tiny bit of beefsteak - soak it in potash solution, in order to dissolve the thready, fibrous "connective tissue" that binds the fibres together, spread the bit of muscle out, and look at it under a microscope, and then you will see the individual fibres - the cells - as plainly, and even much more plainly, than you can see the individual cells in the tissue of an orange. In the human body the cells of some tissues, like the skin and hair, lie in layers, cells of the topmost layers being flattened into scales; the cells of others are long drawn out as in muscles, the cells of others, such as the liver, the stomach and many other glands, are arranged so as to form tiny tubes, invisible to the unaided eye; and the cells of other organs or parts, like the spleen, are crowded together somewhat after the . fashion of the orange. Even the bones consist of living cells, together with substances manufactured by the cells. It is believed - and it is known for many of the cells - that all the cells of the body are short-lived; that some of them are continually dissolving and are carried away by the blood, but that they leave their descendants behind, just like a community of men: so that while the individual cells may pass away, the community of cells - the organ, or the tissue - continues to live. This is perhaps generally true - with one great exception. That exception is the nerve cell. The nerve cells do not die, and they do not reproduce themselves. The nerve cells of a man in his old age are identical with the nerve cells of infancy. From the time that nerve cells make their first appearance in the growing organism long before birth and on until death, they retain their individuality. They do not reproduce themselves and dissolve, as the other cells do. In short, nerve cells are in many ways a remarkable exception to the common laws of cell life; and nervous tissues - as we shall presently see - occupies a singular and wonderful position among tissues in general, and is exempt in many ways from the dangers and diseases that threaten all the other tissues of the body. The nerve cells are the rulers of all the other cells of the body - the masters; they bid all the other cells - they force the other cells to do their particular work. They force the muscles to contract; they regulate the flow of the blood in the arteries and veins; they stir up the gland cells - such as those of stomach and liver - to secrete the products of these organs; they control the nourishment of all the various parts of the body ; and they alone protect the body from a thousand dangers which, without the ceaseless watching and sleepless vigilance of the nerve cells (for these cells work during sleeping and waking) would flow in upon the body and destroy its life. The body may be likened to an ocean steamer of which the nerve cell is the owner, captain, navigator, pilot and eternal look-out man all in one. All the other cells of the body are the obedient crew and ship at one and the same time. I will return to this subject a little later. The same nerve cells with which a man is born last him throughout his life. This is not true of the other cells of the body. And this fact has an important bearing on the treatment of disease, and especially upon the osteopathic method of treating disease. Other cells of the body may be injured or even destroyed, and they are replaced by the generation of new cells of their kind. But if the nerve cells are permanently injured or destroyed by the long use of drugs or other destructive agents, they can never be replaced by new nerve cells and must remain permanently injured as long as the individual lives. Thus, too, it is readily seen that, as the nerve cells rule the body in all its functions, the osteopath, who controls the nerve cells through their great clearing house, the spinal cord, and indirectly, the brain, has his finger, so to speak, on the switch-board of all these various functions which are directly under control of the nerves themselves. SCHWANN'S CELL DISCOVERY WAS A FORERUNNER OF OSTEOPATHY Now while it is true that all animals and plants are built up of cells, we find in Nature single cells that live alone - the unicellular, or one-celled animals and plants. Countless billions of these single cells - each an animal or plant in itself - can be found in the water of ponds and pools. Bacteria - the so-called "germs", a few of which produce disease when they lodge in the body and multiply there - are exceedingly minute single cells: as if an orange cell were to be reduced to, say 1-50,000 or 1-25,000 of an inch, and were to multiply itself all alone without association with its fellow cells. So, too, we find innumerable single animal cells that live in water, or damp places, all of which are visible only in the microscope. When you see under the microscope the wonderful, the almost intelligent conduct and maneuvering of one of these exceedingly small animal cells, you are deeply impressed with the littleness and magnitude of Nature. Remember, now, that these little single-celled animals were well known before

Schwann made his discovery that the human body was only a great co-ordinated

mass of tiny individual animals, packed together, put together, strung and woven

together in inconceivable complexity and unthinkable numbers, and you may have

some idea of how startled the world was when men were first informed of that

fact. It was really an almost incredible thing; and it is by no means a comfortable

thing; and to be told that one's brain consists of billions of individual microscopic

animals; all working together like a perfect trained army. Yet, such is the

fact; and when Schwann announced that fact in 1839 he was unconsciously laying

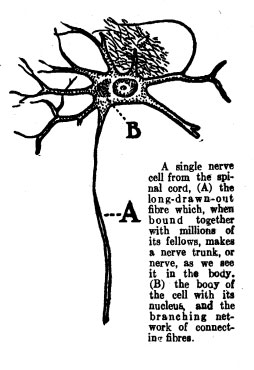

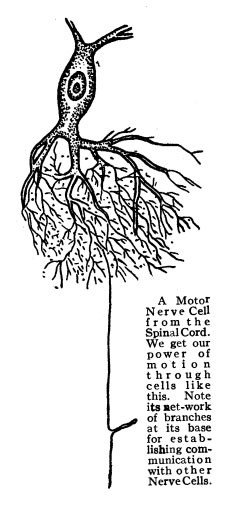

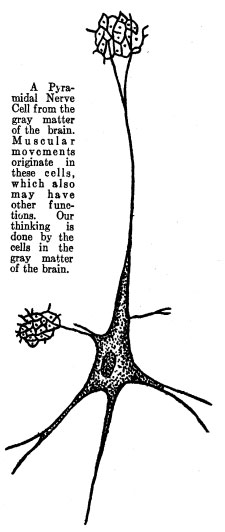

the foundations of the modern science and art of osteopathy. If you take a little piece of the spinal cord, or spinal marrow, of an ox, or any other animal (a fish does excellently) and let it soak over night in weak alcohol or chloral hydrate, and then mash a tiny bit of it between two pieces of thin glass and look at it in a microscope, you will see a sight that should not only startle and amaze you, but should instruct you as well. You will see nerve cells, pretty much as they exist in your own spinal cord - pretty much as they exist in the living brain and spinal cord of a man. Wonderful things they are. There is an irregularly-shaped central body of a dull grayish color, like ground glass, from which stretch forth in many directions, long sinuous arms, like the "feelers" of a cuttlefish. In the middle of the central body is a round body that looks like an eye. It is not an eye. It is the vital organ of the nerve cell, and if some carmine has been mixed with the bit of spinal cord this round eye-like body in the center of the nerve cell will be stained red. This is the nucleus of the cell (and all cells of every kind have a nucleus). The nucleus is the vital part of the cell and upon its life the life of the whole cell depends. All the "feelers" thrown out by the nerve cell are richly branched, like the limbs of a tree, breaking up into minute twigs; all with one exception. This exceptional "feeler" (and these processes from the nerve cell are literally and truly "feelers") has few branches and, unlike the other "feelers" (technically called dendrites from the Greek word for tree), it does not terminate near the cell body but continues on for enormous distances. This long feeler is called the "fibre" and in company with thousands of other fibres from other nerve cells in the spinal cord, it runs out of the tube formed by the vertebrae of the backbone, and forms its tiny part of what is called a nerve. The nerve cells are in the spinal cord, and the fibres leave the cord (or the brain, for the brain is built up in the same way of cells) and in the great cables of fibres called nerves the fibres run to all parts of the body. The fibres constitute the white matter of nervous tissue, so called because of a fatty substance which surrounds and insulates the fibres, and is called the "white substance of Schwann", Schwann having discovered it. This white sheath is also called by other names, but the white color of nerve is due to the white fatty sheath that surrounds each individual fibre. A nerve fibre bound up with thousands of others in a nerve will run from the cell in the cord without a break clear to the finger or toe tip, where it ends in the skin. If you prick the skin of the finger the impulse is carried up the fibre to the cell in the cord, and there the cell passes the impulse to another nerve cell, and so on up to the gray matter (the cells) of the brain, where the impulse is "felt" as sensation. To convey some practical notion of the real size of the nerve cell together

with the length of some of the longest of the fibres, we may compare it with

a much larger object. There are nerve cells in the spinal cord about 1-100th

of an inch in diameter or less with minute fibres coming from them, so small

as to be visible only in the microscope. Many thousands of these fibres

are gathered together and bound tightly with connective tissue so as to form

the cable-like nerve trunks which pass out of the tube-like cavity of the backbone.

These cables of nerve fibres and their cable-like branches - the nerves - vary

in thickness from the diameter of a lead pencil down to a much smaller size,

and after they leave the backbone they break up into smaller branches which

supply the muscles and skin of the upper and lower parts of the body, giving

off smaller and smaller bundles of fibres as they recede from the spine, until

finally the nerve is broken up into branches no longer visible except in the

microscope. These invisible bundles of fibres ultimately branch until they separate

into the still smaller individual fibres which connect with almost all the cells

of the tissues and stimulate them into action. It is the little nerve fibres

that cause the muscle cell to contract, the gland cell to secrete, and so on.

The nerve cells and their intercommunications in the human organism make up a system which probably possesses more apparatus and contains more mysteries a hundred-fold than all the electric systems of our country. The spinal nerves furnish the muscles and skin with the fibres that give motion and sensation to these organs. In the skin the fibres break up into still smaller fibrils, and end in strange looking bulbs, which furnish the skin with organs of touch. Some of these nerve endings, as they are called, are sensitive to cold only; others to heat only; others to touch only; and you can prove this by lightly touching the skin here and there with a cold pencil point or blunt pointed metallic rod, and noting the "cold spots" and so on. The skin is crowded so thickly with these nerve endings that even if all the other tissues of a man were wiped out - if he had nothing but his nervous system left - you could still easily recognize his face from the nerve endings alone. Now as each sensitive ending of a fibre has a corresponding fibre which runs to some muscle fibre, the sensory and motor apparatuses of the body work in perfect harmony. If the skin of the toe be pricked the impulse travels to the cord along a fibre of sensation and is there transferred to motor cells which send impulses to the muscles that move the leg, and the foot is instantly withdrawn. This is called reflex action and when the physician taps below the knee of his patient to "test his reflex" he is using this mechanism. If we could dissolve away all the tissues of the body except the nervous system, there would be left a phantom of a man whom we could easily recognize and identify from the nerve endings in the skin. So that we thus see that the nervous system is ever on the watch at the farthest outposts for danger to the body. Through these millions of microscopic sense organs in the skin, that great

mass of nerve cells and fibres called the brain, is instantaneously warned of

all danger. The nerve fibres of the ear, of the nose, of the tongue and of the

skin generally, serve the double purpose of assisting the body to get its food,

to enjoy all pleasurable things whatsoever, to stimulate the body to move about

from place to place, or to move the muscles without change of location. But

these wonderful sense organs do more. They bring instant warning of danger.

They tell us when to fly from danger, when to avoid the sources of danger

in disagreeable odors, sights, sounds, or tastes, when to seek refuge from the

cold or heat, and in every movement of the body guide it and direct it aright.

The nerve endings in the skin sound the alarm from dangers without, and the

nerve endings in the internal organs and parts warn us of danger from within

by reporting to the brain every abnormal, or nearly every abnormal, condition

that invades us. Thus we see that the nervous system with its great shadowy,

veil-like mantle of nerve endings, acts like a protecting vapor to the body,

and, by means of the voluntary muscles, which are the mere slaves of the brain

and the spinal cord, commands the body to move towards and do things that give

pleasure and comfort, and to move away from and to avoid doing things that bring

discomfort or pain. ALL OTHER STRUCTURES VASSALS OF THE BRAIN AND NERVES The brain and the nerves are the masters of the body. All the other organs and parts are slaves. And to give pleasure and comfort to itself the brain compels all the other organs and tissues to do its will. This will is, as a rule, directed so that when the brain and nerves are best served, the rest of the body is best served also. The best good of the brain and the nerves, therefore, is as a general rule, the best good of the slave organs and tissues too. But this, unfortunately, is not always the case. When the will and desires of the nervous system are not in harmony with the general welfare of the body, the body suffers. As the nerve tissue is the absolute master, the muscles must obey it, even when its mandates are destructive or insane. Therefore the nervous system, to gratify its own wants, will often destroy the useful slaves that minister to its needs. Like the soldiers in the fatal charge at Balaclava, the muscles and the other tissues obey without question. Theirs not to make reply, So the nervous system, to gratify its capricious and destructive desires, often compels the muscles to feed the body with poisonous drugs and stimulants and to do other things that not only destroy the slaves, but in the end the master, also, that is served and nourished by the slaves. The stomach, the liver, the kidneys, the pancreas, the intestines, the lungs and the other glands, and above all the voluntary muscles, are often ruined and wrecked by the intemperate or abnormal desires of the nervous system. The brain, seated upon an imperial throne, whose mandates are instantly and absolutely obeyed, is often an insane Nero dealing death and ruin around him and ending as only such insane tyrants can end, in death and destruction for himself. There is, however, another view of the nervous system in which the blame cannot be laid upon the nervous system itself. The nervous system, in spite of all its superb machinery of self-protection and self-gratification, can be injured in many ways, and not receive warning to avoid the danger. The nervous system, for example, may be compelled to work overtime. It, too,

may be a slave in its turn; and in very fact the nervous system, with the remainder

of the body, is itself a slave to a power higher than itself. This power may

be single or two-fold. It may consist of defects or faults in the heritage of

the nervous system itself. Or it may consist in the defects and faults that

have been inherited by the other organs and tissues from parents. These would

be defects of inheritance. The defects may be due again to the circumstances

in which the individual human being, or other organism, is compelled to live.

These would be defects of environment. But a normal nervous system, surrounded

by defective organs is really a nervous system in an unhealthy environment.

So we see that, given a naturally sound nervous system, such a nervous system

may suffer from being lodged first in a body the organs of which are unhealthy

because of unhealthy parents, or because of disease due to malformations, mal-alignments

or mal-adjustments in the structure of the tissues that surround the nervous

system, or by poisons in the body, which, although they may not affect the nervous

system itself, do disable the slave tissues and make them incapable of obeying

the orders of the nerves, even when the orders are given with clear enunciation

and the best intent for the common good. Such a nervous system would be disabled,

more or less, by the defects of its organic environment; by the defects in the

tissues, the organs, and the fluids of the body in which the healthy normal

nervous system is lodged. It is truly wonderful how perfectly resistant to disease or disorder of any

kind the nervous system is! Ages of development and necessity have successively

selected for survival only the most strongly resistant nervous systems, so that

very few weak nervous systems remain. All our predecessors - or nearly all -

that had weak nervous systems were wiped out before they could get children.

Therefore, only the strongest - the most immune - nervous systems survive. This

is the "survival of the fittest" and the great law of natural selection is seen

best exemplified in the security, the strength, the immunity, the imperial power

and sanctity of brain and nerve in all the bewildering and manifold forms of

life. When a man, or other animal, is starved to death, the nervous system is

the very last to suffer from loss of weight. All the tissues, all the organs,

give up their substance first to the brain and nerves, and next to the muscles.

This, you see, is good policy on the part of Nature, for the reason that if

the nerves suffered and lost power, they could not stimulate the muscles to

move about, secure food, and bring it to the mouth. In starvation, the body

weight is reduced two-thirds before the nervous system loses a grain's weight

of substance. Very few germs attack nerve tissue. The nerves are attacked by

the poison of the tetanus germ, and by the germ of hydrophobia. But the number

of germs and germ poisons which attack nerve tissue is comparatively small.

So-called "disorders of the nerves" are really not nerve disorders at all, but

the efforts of the nervous system -the frantic commands and over-activity of

the nerves - to restore order to the disordered body in which they find themselves.

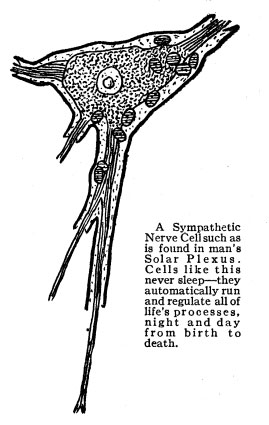

The cure for all toxins in the body lies in the fluids and tissues of the body itself ! BODY'S CHEMICAL ACTION UNDER CONTROL OF THE NERVES What, let us ask, is a "healthy" man? The answer is, a healthy man is an animal the cells of whose organs and tissues have the power of full and instantaneous response to the commands of the nervous system, when these commands are directed for the good and the comfort, not only of the brain and nerves themselves, but for the ease and comfort of the other tissues also. Recall, now, that the nervous system consists of microscopic cells with long tiny microscopic fibres, that often at long distances from the nerve cells themselves, connect up with all the principal other cells of the body. When you are told that the minute invisible fibres of the nerve cells in the brain and cord are connected with other nerve cells in the body cavity called the sympathetic (or involuntary) nerves, and that these involuntary cells have fibres that ramify infinitely to each individual cell of all the organs - of the digestive, the genito-urinary, the respiratory systems - and to each individual cell of the heart and the blood vessels (for the heart and the blood vessels, too, are built up of cells); and that every cell of every other important organ, such as the mysterious "ductless glands" like the thyroid, the mysterious ovaries and testicles with their unknown secretions that affect the health and well being of the entire body, the mysterious suprarenal glands, and other organs of that peculiar kind - when you are told all this, you will come to a slight realization of the tremendous sway which the nervous system has over the infinitely intricate chemical life of the body. The cells of the organs cannot act unless bidden by the nerve fibres. If the cells are poisoned by toxins, whether from the body cells themselves or from invading germs, the mandates that pour along the nerve fibres from the nerve cells, bidding the organ cells to secrete, or bidding other cells do other things, are blocked ; and finding their mandates blocked, the nerve cells overexert themselves in extraordinary commands to the cells of the other organs to do what the other organs cannot do because of the poisons that bathe them all around. Now how does the osteopath answer the question which the body of his patient puts to him? If the blocking of the commands of the nerve cells be due to some impingement

on the nerves by reason of a faulty articulation, or an over-tension or congestion

of the ligaments and muscles, or other maladjustment of the spine, or elsewhere,

he corrects the maladjustment, removes the block, and the nerve, which was healthy

enough all the while, can now convey its message to the organ cell - which was

also healthy all the while; and the "disorder" is cured. |